How a Browser Renders a Web Page

As a developer, to create fast and reliable websites, it's crucial to understand every step a browser takes to display a web page, as each can be considered and optimized during development. This post is a brief overview of this process.

The process can be broken down into the following main stages

- Parsing HTML into DOM

- Fetching External Resources

- Parsing CSS and Creating CSSOM

- Executing JavaScript

- Combining DOM and CSSOM to Construct the Render Tree

- Layout Calculation and Painting

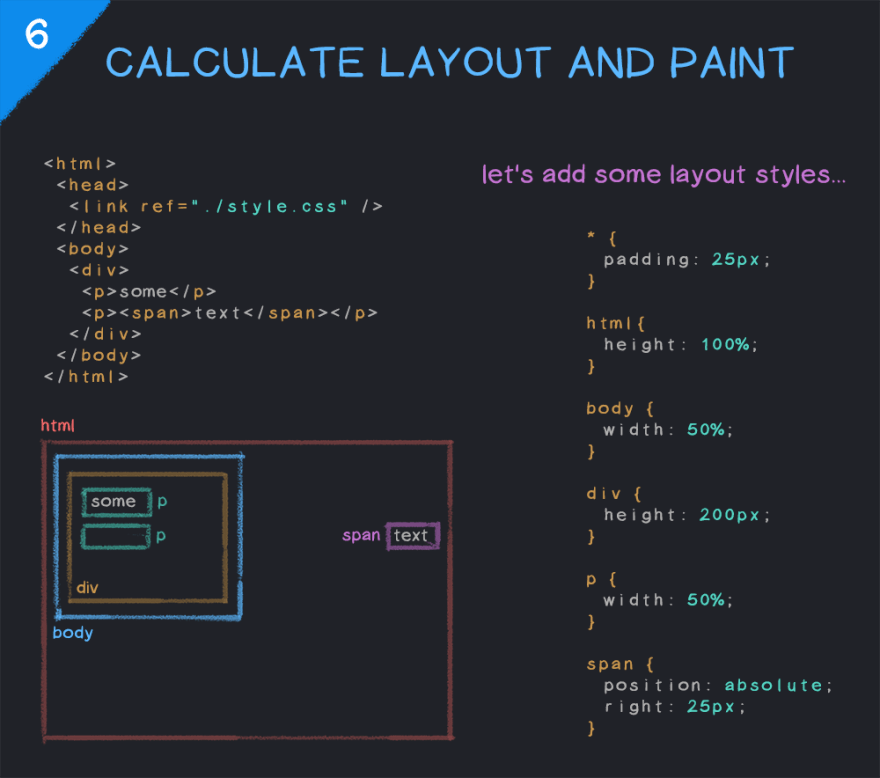

Parsing HTML

When the browser receives an HTML page from the network, it parses HTML into the Document Object Model (DOM). It breaks down HTML into tokens, representing start tags, end tags, and their contents. From this, the browser constructs the DOM.

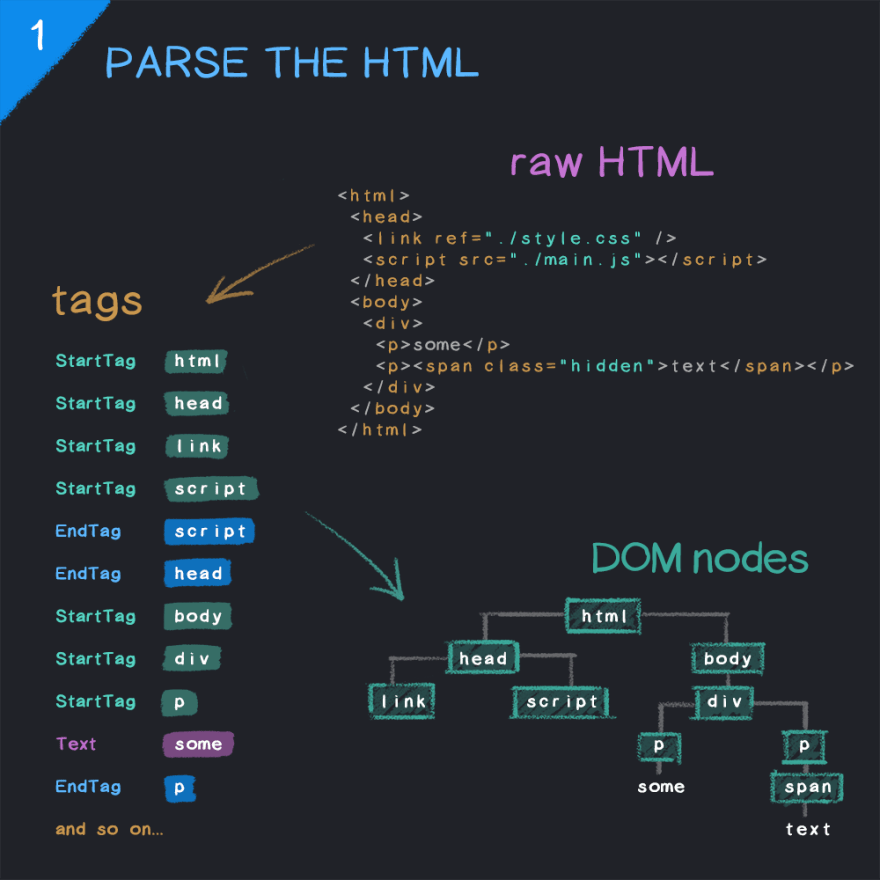

Fetching External Resources

When the parser encounters an external resource like a CSS or JavaScript file, it pauses to request these files. The parser will continue when CSS starts loading, although it will block rendering until it's loaded and parsed (more on this later).

JavaScript files are a bit different - by default, they block HTML parsing until the JavaScript file is loaded and then parsed. There are two attributes you can add to script tags to improve this: defer and async. Both allow the parser to continue while the JavaScript file loads in the background, but they function differently in how they are executed. More on this:

defer means the execution of the file will be deferred until after the document has been parsed. If multiple files have the defer attribute, they will execute in the order they were discovered in the HTML.

<script type="text/javascript" src="script.js" defer>

async means the file will execute as soon as it's loaded, which can be during or after the parsing process, and thus the order in which asynchronous scripts are executed cannot be guaranteed.

<script type="text/javascript" src="script.js" async>

Moreover, modern browsers will continue to scan HTML while it's blocked and "look ahead" to see what external resources are defined further on, then load them. How browsers do this varies, so it's unreliable to expect them to behave in a specific way. To mark a resource as important and thus more likely to be loaded early in the rendering process, you can use the link tag with rel="preload".

<link href="style.css" rel="preload" as="style" />

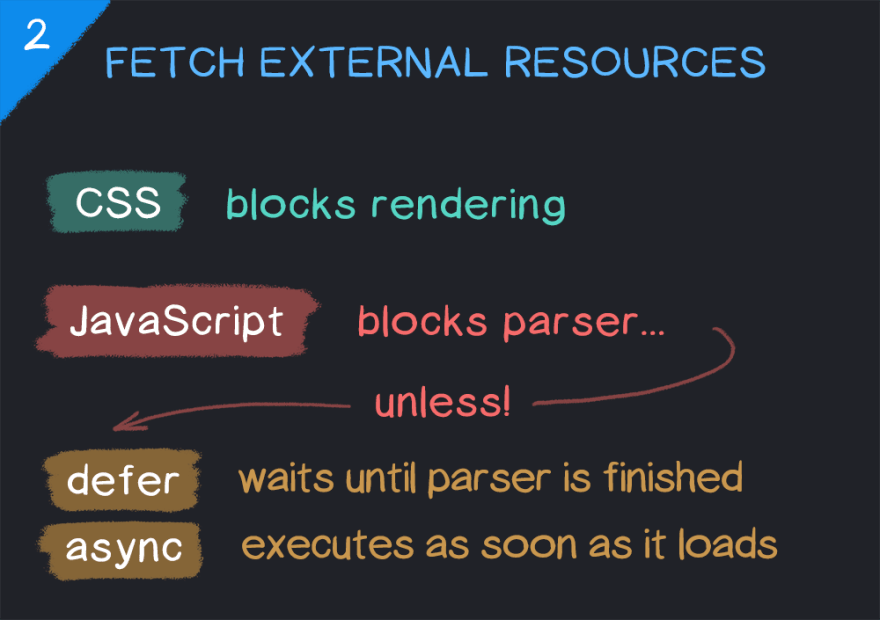

Parsing CSS and Creating CSSOM

CSSOM is a map of all CSS selectors and their corresponding properties for each selector in a tree format with root, sibling, descendant, child elements, etc. CSSOM is very similar to the Document Object Model (DOM). Both are part of the rendering path, which is a series of steps that must happen for a website to be rendered correctly.

CSSOM, together with DOM, is necessary to build the render tree, which in turn is used by the browser to lay out and paint the web page.

Like HTML and DOM, when CSS files are loaded, they need to be parsed and transformed into a tree - this time, CSSOM. It describes all the CSS selectors on the page, their hierarchy, and their properties.

CSSOM differs from DOM in that it can't be constructed incrementally, as CSS rules can overwrite each other due to specificity. This is why CSS blocks rendering, as until all CSS is parsed and CSSOM is built, the browser can't know where and how to place each element on the screen.

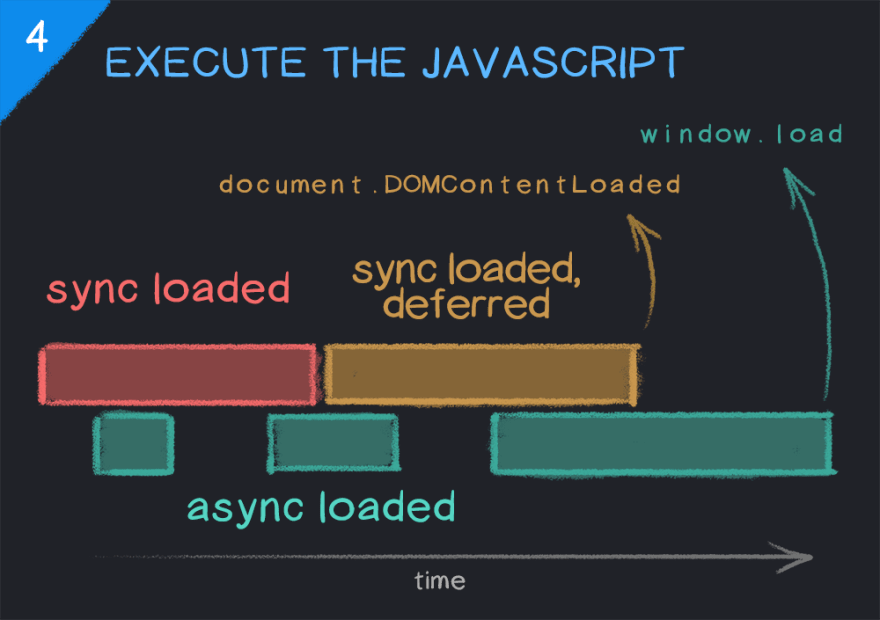

Executing JavaScript

Once synchronously loaded JavaScript and the DOM are fully parsed and ready, the document.DOMContentLoaded event is fired. For any scripts that require access to the DOM model, such as to manipulate it or listen for user interaction events, it's recommended to wait for this event before executing the scripts.

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', (event) => {

// You can now safely access the DOM

});

And after everything else, like asynchronous JavaScript, images, etc., has finished loading, the window.load event is fired.

window.addEventListener('load', (event) => {

// The page has now fully loaded

});

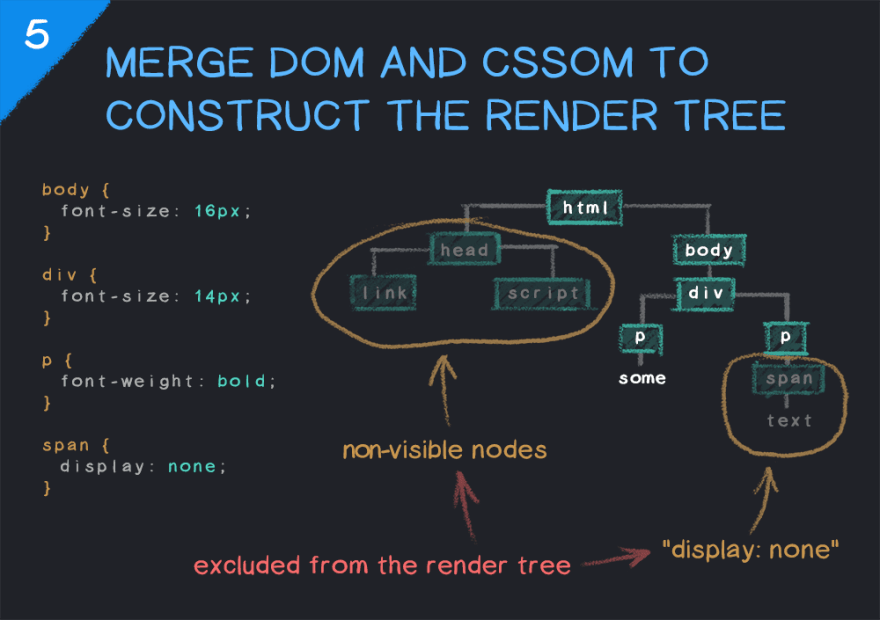

Combining DOM and CSSOM to Construct the Render Tree

The render tree represents the combination of the DOM and CSSOM, and what will be rendered on the page. It doesn't necessarily mean that all nodes in the render tree will be visually present, for example, nodes with styles like opacity: 0 or visibility: hidden will be included and can still be read by screen readers etc., whereas those set to display: none will not be included. Additionally, tags like <head> that don't contain visual information will always be skipped.

Different browsers have different rendering engines, just as is the case with JavaScript engines.

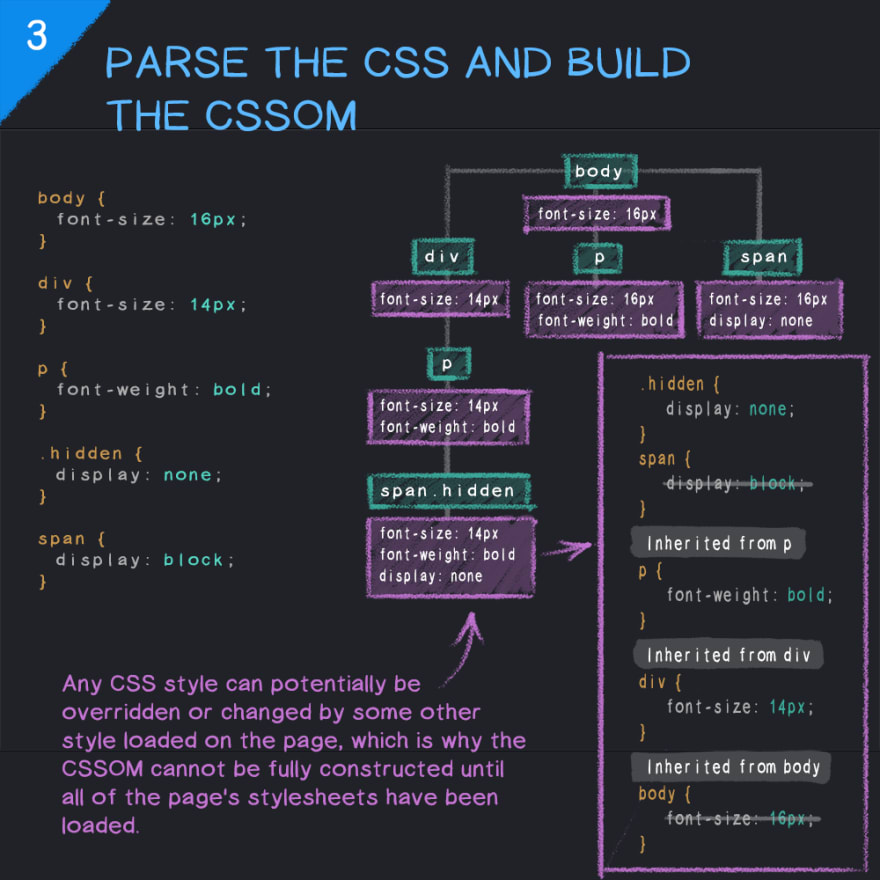

Layout Calculation and Painting

Now that we have the complete render tree, the browser knows what to render but not where to render it. Hence, the layout of the page (i.e., the position and size of each node) needs to be calculated. The rendering engine goes through the render tree from top to bottom, calculating the coordinates at which each node should be displayed.

Once this is done, the final step is to take this layout information and paint the pixels on the screen.

Et voilà! In the end, we have a fully rendered web page!